The NAACP and The Nation Investigate

As the press began to turn on the U.S. occupation of Haiti after Wilson's speech on self-determinism, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People sent field secretary James Weldon Johnson to conduct an investigation into conditions. Johnson published his report and wrote of the occupation many times for the NAACP and The Nation, a weekly progressive magazine. Between 1918 and 1932, The Nation published over 50 articles about the U.S. occupation of Haiti. The work done by the NAACP and The Nation helped raise awareness of injustices in Haiti amongst the American people and led to a congressional hearing into the occupation. These selected reports and articles provide a brief look into some of the responses by anti-occupation activists.

"The Truth about Haiti: An NAACP Investigation" — James Weldon Johnson, 1920

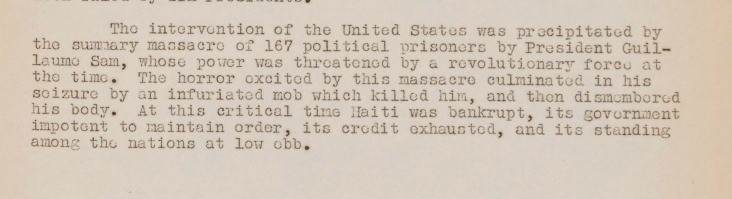

In his investigative report, James Weldon Johnson, field secretary for the NAACP, reviewed the three main reasons that the United States used to justify occupation over Haiti. His report said that Haiti was the second American republic to gain independence and that it had maintained independence for over 100 years until U.S. intervention in 1915. He claimed that nearly 3,000 Marines occupied Haiti and in that five-year period over 3,000 Haitians had been killed. According to the United States, it was necessary to invade Haiti due to anarchy and bloodshed, unfitness to rule, and benefits from U.S. occupation.

- Alleged Anarchy — Marines landed in Haiti following the overthrow and assassination of President Guillaume Sam, but the U.S. had been attemping to establish control over the nation for almost a year. There were three diplomatic efforts to do so, with the third occurring in May 1915 under Envoy Extraordinary Paul Fuller, Jr. The goal was to have Haiti sign an agreement similar to the treaty established with Santo Domingo. Although President Sam had been overthrown, there was no evidence of threats to Americans in Haiti, and it was reported to be calm following the coup.

- Fitness to Rule — There have been many sources of propaganda produced by the French against the Haitians, claiming they are barbaric, satanists, and cannibals. From personal observation, Weldon writes that Haitians are not dirty, lazy, or ignorant. Many are illiterate, but that is due to the fact that the majority of the population speaks Creole, not French, and Creole is not a written language.

- American Benefits — Johnson was only able to find three things the Americans had done for Haiti: improvement of the public hospital in Port-au-Prince, enforcement of rules of modern sanitation, and the building of a new road from Port-au-Prince to Cap-Haitien, although it was built under forced labor. There had been no efforts towards improving or advancing public education. American Marines were violent towards Haitians, raped women, and were prejudiced. This prejudice was largelly born from the fact that many of the officials were white Southerners.

"Self-Determining Haiti: The American Occupation" — James Weldon Johnson, The Nation 111, August 18, 1920

In this edition of The Nation, Johnson continues to delve into the underlying intentions of the U.S. occupation of Haiti. He compared the previous negotiations under Paul Fuller, Jr. and the current treaty that Haiti had been subjected to. According to Johnson, the Haitian president Theodor Davilmar denied the agreement proposed by Fuller on December 15, 1914. Not even a year later, U.S. Marines invaded Haiti, and according to Johnson, "The overthrow of Guillaume did not constitute the cause of American intervention in Haiti, but merely furnished the awaited opportunity."

By September 16, 1915, the Haitian government had signed the convention with the United States, but while the Fuller convention had more equal terms, the occupation convention demanded very much from Haiti while the U.S. contributed very little. A new constitution was also drafted, and the Haitian legislative body did not want to approve it. This led to the assembly being dissolved by military force.

One of the main points of contention in the new constitution was a special article relating to the occupation which provided that:

- All acts of the Government of the United States during its military Occupation in Haiti are ratified and confirmed.

- No Haitian shall be liable to civil or criminal prosecution for any act done by order of the Occupation or under its authority.

- The acts of the courts martial of the Occupation, without, however, infringing on the right to pardon, shall not be subject to revision.

- The acts of the Executive Power (the President) up to the promulgation of the present constitution are likewise ratified and confirmed.

Following the ratification of the new constitution, Haitian President Dartiguenave fully ackowledged the powerlessness of his position and the Haitian government. The press was under extremely strict censorship and was not allowed to publish anything critical of the occupation. According to Johnson, "The Haitian people justly complain that not only is the convention inimical to the best interests of their country, but that the convention, such as it is, is not being carried out in accordance with the letter, nor in accordance with the spirit in which they were led to believe it would be carried out."

"Self-Determining Haiti: What the United States has Accomplished" — James Weldon Johnson, The Nation 111, September 4, 1920

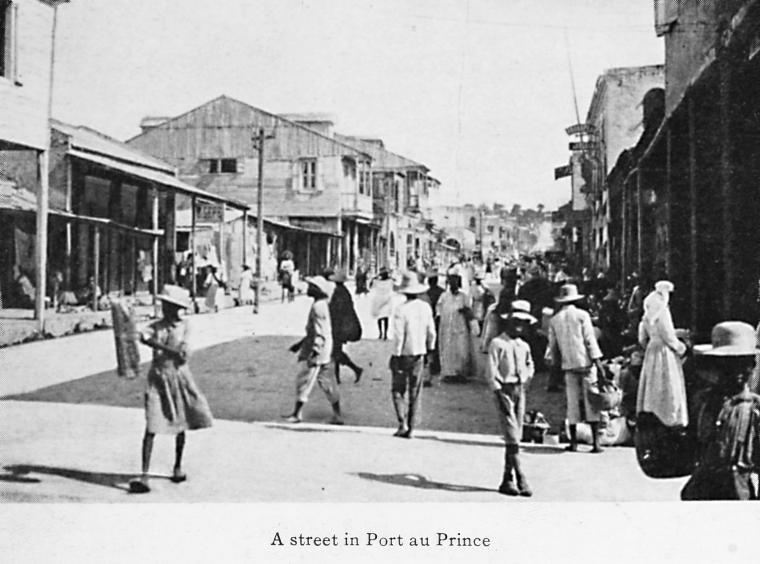

In the second article in his Haiti series, Johnson reviews what the occupation has accomplished in improving Haiti. Sanitary regulations were improved in Port-au-Prince, although Johnson argues that cleanliness and health were not pressing issues and that the Haitians were a very clean people that bathed often. There were no pavement efforts in Port-au-Prince, but a new road was built from Port-au-Prince to Cap-Haitien, although Johnson argued that it was most likely built as a military highway, not to ease travels for Haitians. Men were also conscripted to build the road, and many of the men that managed to escape conscription became members of rebel cacos. Marines were permitted to shoot rebels on sight. The Haitians were disarmed by the Marines, and they were later supposed to replace white Marines in the gendarmerie, but the transition was slow, almost nonexistent. Lastly, there had been no improvement of the educational system, as had been done in Puerto Rico, Cuba, or the Philippines.

"Self-Determining Haiti: Government of, by, and for the National Bank" — James Weldon Johnson, The Nation 111, September 11, 1920

In the third installment in his Haiti series, Johnson focused on some of the underlying motivations for invading Haiti, namely those of government constituents. He argues that Roger L. Farnham, vice president of the National City Bank in New York, was a crucial figure in pushing the invasion of Haiti. His bank controlled the Banque Nationale d'Haiti throughout the occupation. Farnham was also appointed receiver of the National Railroad of Haiti, and he was expected to receive a $5 million sugar plant in Port-au-Prince.

John Avery McIlhenny was appointed Financial Advisor to Haiti but lacked experience and training in such matters. In 1920, a new agreement was drafted that would give the U.S. control over importing and exporting in Haiti, as well as:

- A modification of the Bank Contract agreed upon by the Department of States and the National City Bank of New York.

- Transfer of the National Bank of the Republic of Haiti to a new bank registered under the laws of Haiti, to be known as the National Bank of the Republic of Haiti.

- The execution of Article 15 of the Contract of Withdrawal prohibiting the importation and exportation of non-Haitian money except that which might be necessary for the needs of commerce in the opinion of the Financial Adviser.

Until this new agreement was signed, McIlhenny refused to distribute the salaries of the president, ministers of departments, members of the Council of State, and the official interpreter. As of the writing of this article, the salaries had not been paid since July 1.

"Self-Determining Haiti: The Haitian People" — James Weldon Johnson, The Nation 111, September 25, 1920

In the final article of this series, Johnson takes the time to describe the country of Haiti and its people. He recounts his visit to Port-au-Prince and how beautiful a city it was and how cultured the people were. Haitians in the countryside are humble and kind, often living in one-room huts, and all Haitians have a habit of cleanliness. They are not lazy, and their only handicap is a lack of a written language. While Haiti has had bloody revolutions, it is important to remember that they are often dramatized and backed by foreigners. Johnson reminds readers that Haiti's history cannot be compared to the United States or England but to other Latin American countries. He finishes by writing:

And this is the people whose "inferiority," whose "retrogression," whose "savagery," is advanced as a justification for intervention — for the ruthless slaughter of three thousand of its practically defenseless sons, with the death of a score of our own boys, own today as the author of The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man. Fiat justitia, ruat coelum!

Woodrow Wilson to William Jennings Bryan

Plans to intervene in Haiti and establish a treaty were planned long before the coup d'etat in July 1915 and the lynching of President Sam, as seen in these letter between Wiilson and Bryan

"Hearing the Truth about Haiti" — Helena Hill Weed, The Nation, November 1921

Helena Hill Weed was an ardent supporter of the United States withdrawing from Haiti, and she often wrote on the topic in The Nation. Along with James Weldon Johnson, Weed was a member of the Haiti-Santo Domingo Independence Society. In this article, Weed summarizes and reviews the Select Senate Committee hearings on Haiti and Santo Domingo.

In the hearings, Roger L. Farnham testified that there was never a plan of development in Haiti and that he believed they were worse off than before the occupation. Admiral William B. Caperton, commanding officer from 1916 to 1917, testified that the United States did not uphold its end of the treaty. Reverend L. Ton Evans, Baptist missionary in Haiti for 28 years, testified that the occupation was unjustified, illegal, and unconstitutional.

The hearings also revealed that an invasion of Haiti had been planned long before the assassination of then-President Sam, and that a treaty was drafted as early as July 2, 1914. During the coup d'etat in July 1915, no Americans had been threatened or were in danger, and the president was overthrown due to the potential signing of a treaty with the United States, as well as his order to kill political prisoners. Despite a lack of violence towards Americans in Haiti, Admiral Caperton was ordered to land troops in Port-au-Prince, although he testified that he was unsure as to why he had been ordered to do so.

After establishing control over the small country, officials in Washington ordered Admiral Caperton to postpone a presidential election until the United States could find a suitable candidate to act as a puppet. Dartiguenave was later elected, and Admiral Caperton was instructed to pressure the Haitian government to sign the treaty. The treaty required Haiti to cede Mole St. Nicholas to the United States, among other stipulations. The Haitian legislative body refused to ratify the treaty, so the United States responded by seizing custom houses, and all income was deposited in National City Bank branches in Haiti for use by the U.S. military. Later on, the Haitian constitution was illegally revised in order to grant foreign powers the right to own land in Haiti.