U.S. Imperialism and "The White Man's Burden"

The United States began to develop an interest in imperialism toward the end of the 19th century and efforts were fully implemented at the beginning of the 20th century. From 1895 to 1915, the U.S. would collect nations from the Caribbean to the Pacific. The question of sovereignty for these people was largely determined by the current thoughts on the rights of African Americans, who were considered second-class citizens and inferior to white Americans. John W. Burgess, American political scientist, wrote

The North is learning every day by valuable experiences that there are vast differences in political capacity between the races, that it is the white man's mission, his duty, and his right to hold the reins of political power in his own hands for the civilization of the world and the welfare of mankind.

By supporting these views at home, imperialists could transfer the same principles to overseas territories and deny the citizens a right to sovereignty and protection under the U.S. Constitution because of their skin color.

William Jennings Bryan to Woodrow Wilson

Letter from Bryan to Wilson outlining foreign policy with Caribbean and Latin-American countries

Telegram Draft to the American Legation of Haiti

Draft by Bryan to the American Legation regarding further relations with Haiti

Many of the United States' imperialist ideals were influenced by three people: Alfred T. Mahan, naval officer and historian; Theodore Roosevelt, 26th President of the United States; and Henry Cabot Lodge, writer and Massachusetts Senator. Mahan developed many of the principles that were touted by Roosevelt and Lodge, especially the idea of the plebiscite. Mahan also believed that the United States should not intervene in nations that did not want its help, but it should also not deny those that want to become a part of the republic. For example, a population of Americans living in Hawaii desired to join the Union, therefore the U.S. had the right to annex it.

The principles of U.S. imperialism revolved around the belief that Anglo-Saxons were far more advanced than other races, especially in terms of developing a political society. It was thought that Anglo-Saxons were the only group competent enough to govern themselves and that the greatness of the political society of the United States should be brought to other nations that could not achieve the same greatness on their own. Roosevelt was a strong believer in these principles, and by 1898, he began to implement a plan of U.S. expansion, which could be achieved by joining Cuba in the war against Spain.

The Spanish-American War lasted from April 21, 1898 to August 13, 1898, and in the Treaty of Paris, Spain gave up their claim to Cuba, ceded Guam and Puerto Rico to the U.S., and sold the Philippines to the U.S. for $20 million. These territories, as well as the recently-annexed Hawaii, were not allowed to learn by governing themselves, like the Anglo-Saxons, because they were "innately incapable" of doing so.

Roosevelt and Lodge "built the fires of imperial adventure" and were largely aided by Senator Albert J. Beveridge of Indiana. Beveridge, like Roosevelt and Lodge, was a nationalist and expansionist. Beveridge believed in

Not self-government for peoples who have not yet learned the alphabet of liberty; nor territorial independence for islands whose ignorant, suspicious and primitive inhabitants, left to themselves, would prey upon one another ... not the flimsy application of abstract governmental theories possible only to the most advanced races and which applied to underdeveloped peoples, work out grotesque and fatal results — not anything but the discharge of our great national trust and greater national duty to our wards by common-sense methods will achieve the welfare of our colonies and bring us success in the civilizing work to which we are called.

In arguments for U.S. imperialism, Haiti was often used an example of "the Negroe's inability to govern himself." Instead of letting their territories follow in Haiti's footsteps, the U.S. would provide administration to their newly-acquired territories. In other words, the U.S. would do the things for the native people that they would not or could not do for themselves. In 1901, Woodrow Wilson wrote that

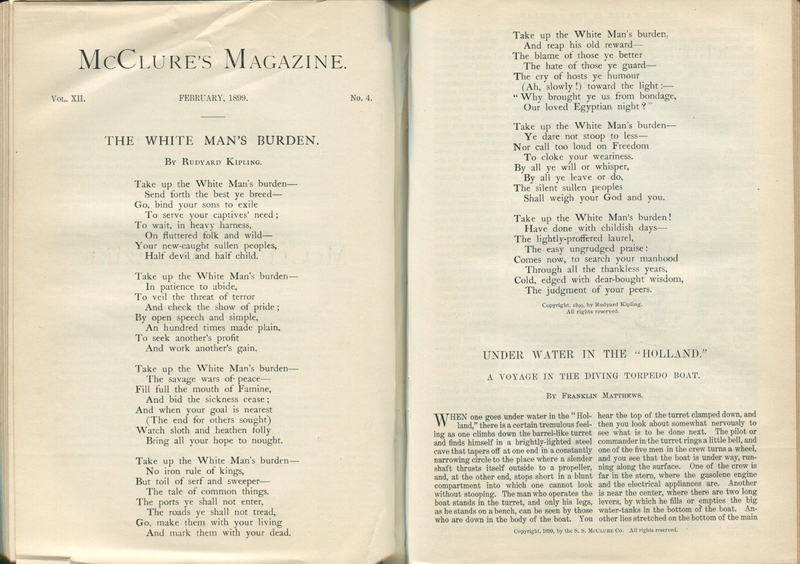

At the time, magazines and articles were important in spreading viewpoints on imperialism, but whether the argument was for or against expansion, they were still largely based in racist ideologies. Anti-imperialists were against adding more people of color to an already-fraught body politic, while pro-imperialists believed people of color were too incompetent to govern themselves, so the U.S. must intervene.

Nations affected by U.S. Imperialism

Haiti was not the first territory to become part of the U.S. effort to undertake "The White Man's Burden," and it was not the last to feel the effects of U.S. imperialism.

Hawaii

- Following an uprising in 1893, rebels appealed to the U.S. for protection and Marines stormed the island, but anti-imperialist president Grover Cleveland withdrew the annexation treaty and desired restoration of Queen Liluokalani to her throne

- Hawaii was re-annexed in 1898 due to its strategic location as a stop-over point between the U.S. and the Philippines during the Spanish-American War

The Philippines

- Acquired in 1898 from the Spanish for $20 million in the Treaty of Paris

- 1899 — policy was pursued by Taft to economically tie the Philippines to the U.S. to the point where they could not feasibly sever the connection

- The Filippino-American War was fought from 1898-1902 following the cecession of the Philippines from Spain to America, which many Filippino independence leaders did not recognize. The fighting led to an estimated 20,000 Filippino soldier deaths and 200,000 Filippino civilian deaths

Cuba

- The U.S. supported republican principles in Cuba but was hesitant to give them complete political independence

- The Teller Amendment in 1898 said that the U.S. would not annex Cuba, only aid them in gaining independence from Spain, then it would withdraw troops

- The Treaty of Paris in 1898 ended Spain's control over Cuba

- The Platt Amendment, passed in 1901, stated seven conditions that Cuba must agree to before the U.S. would withdraw troops

- The amendment allowed for U.S. intervention when necessary and land for naval bases

- The U.S. intervened in Cuba in 1906-1909, 1912, and 1917-1922

- The 1934 Treaty of Relations abrogated the 1903 Treaty of Relations agreed to in the Platt Amendment

Puerto Rico

- Puerto Rico was ceded to the U.S. from Spain in the Treaty of Paris in 1898

- The U.S. and Puerto Rico developed a metropolis-colony relationship

- The Foraker Act, enacted in 1900, allowed for some levels of civilian popular government, but the upper house and governor were still appointed by the U.S. government

- In 1914, Puerto Rican delegates voted in favor of independence from the U.S., but the U.S. Congress deemed it unconstitutional

- The Jones-Shadforth Act, enacted in 1917, granted U.S. citizenship to Puerto Ricans, though the Puerto Rican House of Delegates claimed it was done so that the U.S. could draft Puerto Rican men into World War I

- Puerto Rico is still a territory of the U.S. and holds no voting power

Dominican Republic

- The Dominican government asked for U.S. assistance following revolutions in 1904 and in 1907 a treaty was signed between the two countries

- The U.S. established a military government in 1916

Nicaragua

- The U.S. intervened in Nicaragua in 1912 in order to prevent other nations from building a Nicaraguan canal, as well as to "create peace"

Panama

- The U.S. was given control of the Panama Canal Zone in 1903 after supporting Panama's independence from Colombia

Mexico

- The U.S. fought Mexico from 1910 to 1919 in the Border Wars

- In 1914, the U.S. occupied Veracruz in order to cut off German supplies to Mexico

Honduras

- The U.S. frequently intervened in Honduras to protect American fruit companies

- Interventions occurred in 1903, 1907, 1911, 1912, 1919, 1924, and 1925