Introduction to the U.S. Occupation of Haiti

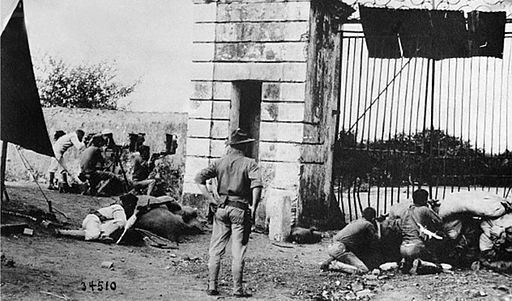

Beginning on July 28, 1915, over three hundred United States Marines were ordered to invade Port-au-Prince, Haiti following a coup and the lynching of President Jean Vilbrun Guillaume Sam. This action by President Woodrow Wilson would begin the 19-year-long occupation of the small island nation of Haiti, which had previously been independent for over 100 years.

Under the guise of restoring peace to the nation, the United States replaced coup leader and current president, Rosalvo Bobo, with a puppet government led by Philippe Sudré Dartiguenave. The Wilson administration submitted a convention to the Haitian government in order to establish the terms of the occupation. In this convention, it was stipulated that:

- Haitian receivership of customs would be established under the control of Americans. This would include an American administrator-general of customs and an American collector in charge of the custom house at each port.

- A native Haitian rural and civic constabulary would be established under the control of Marine Corps officers.

- The United States would be solely responsible for all expenditures of public monies, to the extent necessary to prevent speculation and safeguard the interest of the American people.

- Haiti could not cede land to any nation other than the United States.

- The revolutionary forces would be disarmed.

- The convention would run for a period of 10 years.

This convention was ratified by the United States in September 1915.

After the United States entered World War I, relationships between Haitians and American forces deteriorated due to qualified senior Marine officers being sent to fight in Europe. This led to the appointment of uneducated junior officers in leadership positions.

In 1918, a new constitution was approved by the Haitian people after President Dartiguenave dissolved the legislative body. The constitution was drafted by Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and while it was a fairly liberal document, it did allow for foreign land ownership, something that had been made illegal by the first leader of Haiti following the revolution, Jean-Jacques Dessalines.

Following the end of WWI, the United States continued to occupy Haiti despite President Wilson's support of self-determination and sovereignty. In a meeting of peace delegates in Washington, Wilson said:

We believe these fundamental things: First, that every people has a right to choose the sovereignty under which they shall live ... Second, that small States of the world have a right to enjoy the same respect for their sovereignty and for their territorial integrity that great and powerful nations expect and insist upon. And third, that the world has a right to be free from every disturbance of its peace that has its origin in aggression and disregard of the rights of peoples and nations.

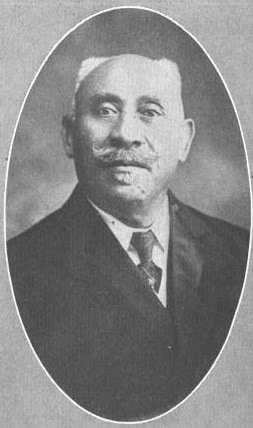

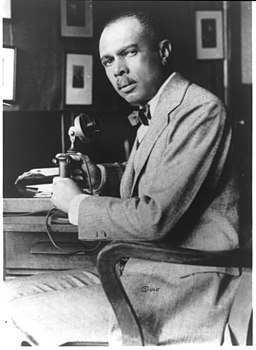

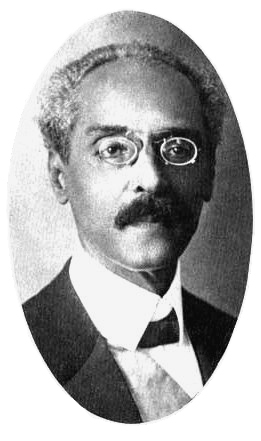

In the fall of 1919, reports became more critical of the occupation of Haiti after it was discovered that the operation was strictly censored and the American press was not accurately representing the situation. American attitudes towards the occupation worsened even further following the release of an NAACP report by James Welson Johnson in 1920 titled "The Truth about Haiti: An NAACP Investigation." His investigation and subsequent articles in The Nation described the corruption, forced labor, press censorship, racial segregation, and violence that was prevalent in Haiti.

Following public outcry, the Senate Committee of Foreign Relations was created in order to investigate the occupation of Hispaniola. The committee returned on December 21, 1921 and deteremined that President Harding should keep the Marines on the island and believed that "the diplomatic representatives and naval forces of the United States made it possible for the Haitian Assembly to sit in security."

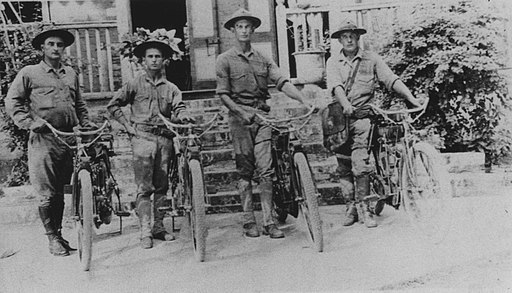

In 1922, Louis Borno was elected as the next president of Haiti, and General John Russell, Jr. was appointed as High Commissioner. The Borno-Russell Government built 1000 miles of road, established a telephone exchange, modernized port facilities, and improved public health facilities. But it was also under Commissioner Russell that many of the abuses against the Haitian people occurred. He was charged with 10 counts of unconstitutional and illegal conduct by the Haiti-Santo Domingo Independence Society for use of military force in enforcing the Constitution of 1918, which allowed for foreigners to have the same rights as Haitians in the courts, for foreigners to own land, and for all acts under the occupation to be ratified and legalized, therefore making it impossible for Haitians to bring charges for crimes committed by Marines.

There was substantial backlash from the American people and government officials against the Select Senate Committee's final report due to its findings that the claims of torture and abuse of power against the United States were unsubstantiated. Utah Senator William King said that

"The people of San Domingo and the people of Haiti have the right to determine their own form of government. It is not our island. It is not under the American flag. It is inhabited by people of a different race, who have lived under different conditions from those prevailing in the United States. They did not invite us there. They do not want us there. It is their island, and the true government on the island ought to be controlled by the people themselves..."

Controversies surrounding the occupation of Haiti continued throughout the 1920s, and in 1929, President Herbert Hoover appointed W. Cameron Forbes as the head of a commission to investigate the internal affairs and conditions in Haiti. The commission found that many of the criticisms and claims against the occupation in 1920 were true, and it recommended that Hoover begin a nine-step plan to pull out of Haiti. In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt adopted the "Good Neighbor" policy and stated that "The definite policy of the United States from now on is one opposed to armed intervention." U.S. Marines withdrew from Haiti in 1934, and the treaty over customs houses expired May 3, 1936.