Occupation Motives

United States interests in the Caribbean increased exponentially after the Spanish-American War in 1898 and acqusition of the Panama Canal Zone in 1903. Beginning in 1900, the U.S. desired political stability in the Caribbean to avoid foreign intervention. The U.S. quickly discovered that the stipulations of the Monroe Doctrine were no longer adequate in protecting such an important area as the Caribbean. Because of this, Theodore Roosevelt developed the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine in 1904. The Roosevelt Corollary stated that the U.S. would intervene at last resort to ensure that other nations in the Western Hemisphere fulfilled obligations to creditors and did not violate the rights of the U.S. or invite foreign aggression to the detriment of American nations. Over time, the Roosevelt Corollary had little to do with economic relations between the Western Hemisphere and Europe, but it was often used as justification for intervention in countries like Cuba, Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic.

Haiti and other Caribbean nations often faced intimidation under Roosevelt's Big Stick Policy, and this was only expanded under William H. Taft. Taft encouraged U.S. investors to replace foreign creditors in Haiti in the hopes that their financial efforts would lead to decreased European influence in the Caribbean. The Wilson administration continued Roosevelt and Taft's policies of domination and stabilization in the Caribbean and eventually used more military force and diplomatic pressure than previous administrations.

In the decision to intervene in Haiti, the Wilson administration was motivated by three primary reasons: military advantages, economic domination, and social and moral development. Originally, William Jennings Bryan, Secretary of State from March 3, 1913 to June 9, 1915, desired elimination of European and American economic interests in the Caribbean loan-sharking business, which often led to loan default-intervention syndrome, in favor of a less exploitative system, but this view was seen as politically unacceptable at the time. Instead, Bryan continued to encourage and support American economic interests in order to eliminate European control in the area.

Much of the State Department policy surrounding Haiti was influenced by Roger L. Farnham, vice president of the National Bank of New York City and of the Banque Nationale d'Haiti, as well as the president of the National Railway of Haiti beginning in 1913. Bryan and Robert Lansing, counselor to the State Department, did not trust or think very highly of the current American ambassador to Haiti, Arthur Bailly-Blanchard, and Bryan had replaced many employees with knowledge of Latin American countries with new appointees. Wilson and Bryan had very little knowledge about Haiti, and there were few experts on the country, so the State Department relied heavily on the word of Farnham.

Military Advantages

Haiti sits in an extremely favorable position in the Windward Passage, a strait between Cuba and Hispaniola that offers a direct route to the Panama Canal. The Windward Passage also connects the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, making it susceptible to European influence, especially in the early 20th century. The U.S. was interested in keeping European powers out of the Caribbean, particularly Germany. Môle-Saint-Nicolas in Haiti, Samaná Bay in the Dominican Republic, and the Dutch West Indies were particularly vulnerable to Germany because the U.S. did not have a strong hold on the local politics.

The decision to intervene in Haiti was heavily based on military considerations. Wilson and Bryan were led to believe that foreign powers were controlling the Haitian government. This was, in part, due to the reports of Farnham, who often exaggerated the role of France and Germany in Haiti to try to force an American intervention. In 1915, he reported that France and Germany were working together to control Haiti, although this is unlikely due to the fact that they were currently on opposing sides of World War I. Despite these fallacies, the U.S. was ready to take control of Haiti. In April 1915, Bryan had written to Wilson that the only questions left in the decision to intervene were the time and the method.

Lansing, who served as Secretary of State from June 9, 1915 to February 13, 1920, did not trust Farnham as Bryan had, but he was a staunch Germanophobe, so the plans to intervene in Haiti continued. In 1915, Lansing desired to add a new "Caribbean Policy" to the Monroe Doctrine, which would allow for forcible U.S. intervention to counter European financial control.

On July 28, 1915, U.S. Marines invaded Haiti after a political coup, but American warships had been alerted to a possible intervention as early as July 1914. A Navy Department document titled "Plan for Landing and Occupying the City of Port-au-Prince," which was drafted in November 1914, months before the invasion in July 1915, reveals that the U.S. was lying in wait for the ideal time to intervene. The report begins:

Situation — The government has been overthrown; all semblance of law and order has ceased; the local authorities admit their inability to protect foreign interests, the city being overrun and in the hands of about 5,000 soldiers and civilian mobs.

Economic Domination

Farnham, as vice president of the Banque Nationale, featured heavily in the economy of Haiti. He served as a mentor to the Banque and was in charge of internal reorganization efforts. Farnham undertook several plans to force Haiti into a customs receivership with the United States. One of the larger plans to do so involved the Banque setting aside a 10 million franc monetary reform fund in order to bolster the value of the gourde, Haiti's currency. The 1910 Banque contract, which offered a 65 million franc loan and the 10 million franc reform fund, also called for the elimination of government currency and forthe Banque to have the sole right of note issue. This would make the Haitian government completely reliant on the Banque. In 1914, the Banque refused to let the Haitian government use the 10 million francs by claiming it was a trust fund.

In 1914, the Banque defaulted on the convention budgétaire, which allowed for the monthly advancement of government funds. Instead, the Banque held all funds until the end of the fiscal year. This caused the Haitian government to float internal loans at exorbitant interest rates. The Banque also had a hand in blocking non-Banque foreign loans to the Haitian government, as well as supporting revolutions. All of these efforts were made in order to weaken the Haitian economy and force it into a receivership.

American companies and investors were also expressing desires for the U.S. to intervene in Haiti. Many investors, like the United Fruit Company, refused to establish themselves in Haiti unless the U.S. stopped the revolutions. In July 1914, the Farnham Plan was drafted, which planned for a U.S. customs receivership in Haiti, but no matter how financially desperate, the Haitian government could not afford to give up national sovereignty. In 1915, Farnham threatened Bryan with a withdrawal of all American interests if the U.S. did not take action. Although diplomatic efforts failed to establish a receivership, Farnham insisted on the U.S. taking control of custom houses. Bryan agreed with him, largely due to the threat of U.S. companies withdrawing from Haiti.

The U.S. intervention in Haiti is considered part of the Banana Wars, which was a period of time between the Spanish-American War in 1898 and Franklin D. Roosevelt's "Good Neighbor" policy in 1934 marked by occupations, police actions, and interventions that were commercially motivated.

Moral and Social Development

Racism played a large part in the justification for intervening in the Caribbean, and Haiti was often used as an example of the detriments of a society ruled by black people. According to Lansing:

At the time, many people believed other races would never achieve the greatness of a body politic established by Anglo-Saxons, so annexation and intervention were beneficial, especially in nations like Haiti that had many political coups and revolutions. As of the landing of the Marines in Port-au-Prince, there had been seven presidents in the past five years, with each leader being killed or overthrown.

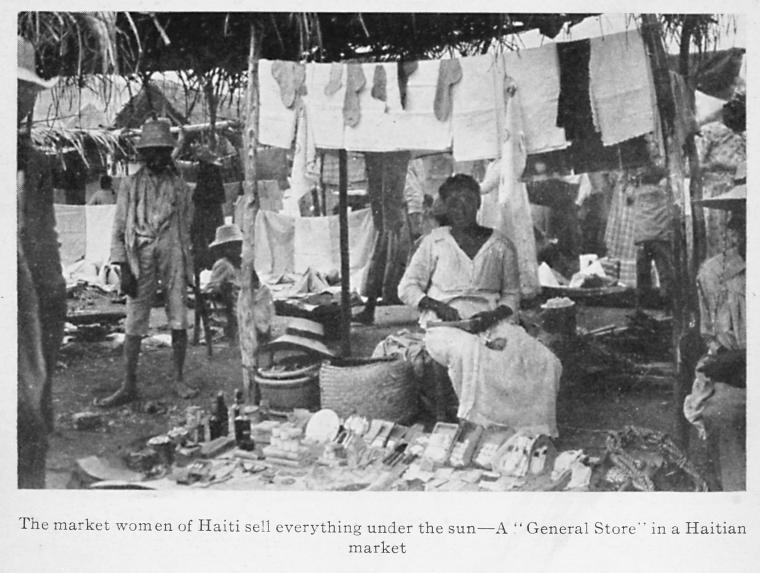

People in Haiti were seen as innately backwards due to their lack of white leadership, lack of a written language, high illiteracy levels, and the practice of vodou. Vodou, known to many as "voodoo," was believed by many outsiders to be a form of snake worship that relied on human sacrifice and superstition. To non-Haitians, the practice of vodou illustrated Haiti's backwardness and incompetence.

During the height of U.S. imperialism, "The White Man's Burden," a poem by Rudyard Kipling, influenced many pro-imperialists into believing their efforts were paternalistic. It was believed that it was the duty or "burden" of Anglo-Saxons to raise their territories to the same level of sophistication as white nations.