A New Treaty and a New Constitution

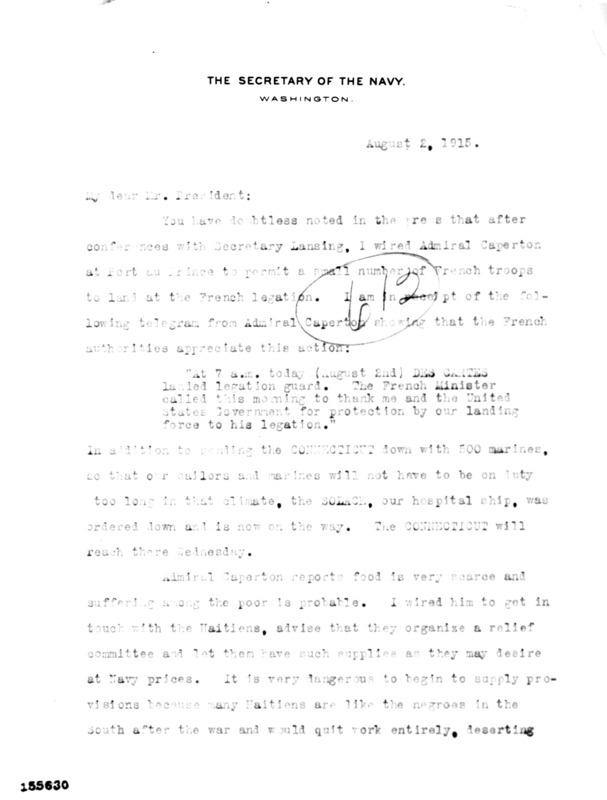

Upon their landing, U.S. Marines were met with hostility from the Haitian people, who were determined to fight the intervention with guerilla warfare. Rebel forces cut off food supplies to Port-au-Prince and other major cities, forcing the U.S. to supply aid, although some U.S. officials, like Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, were worried about providing too much aid. During this initial period, Navy personnel and the Red Cross distributed food and provided medical attention to the Haitians.

Within weeks of the invasion, the U.S. had gained control of all governmental agencies and revenue of coastal towns. Naval officers were assigned to supervise custom houses, but the relationships between Haitians and U.S. officers were strained because of the racial prejudices held by American officers.

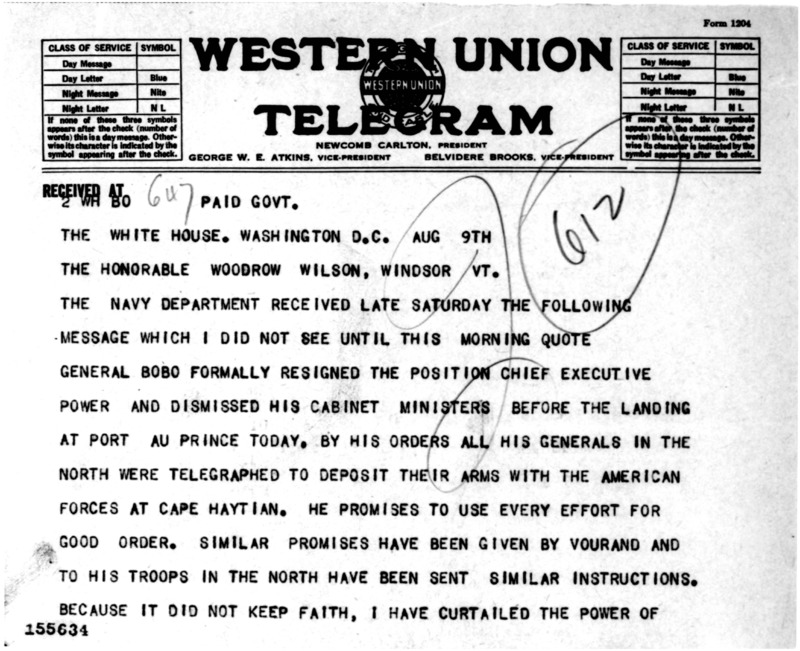

When it came to electing a new president, U.S. officials had a heavy hand in preventing the election of Rosalvo Bobo, who was against the American invasion. In the search for a president, Admiral Caperton asked three respected Haitian politicians — J.N. Leger, Solon Menos, and F.D. Légitime — to take the position, but they had no desire to be a puppet president for the U.S. Leger, the Haitian minister to Washington, defended his position, saying "I am for Haiti, not for the United States; Haiti's president will have to accept directions and orders from the United States and I propose to keep myself in a position where I will be able to defend Haiti's interests." Sudré Dartiguenave was interested in becoming the next president for the client-government but only if the U.S. would provide protection from Haitian rebels. Dartiguenave was elected president August 12, 1915, and he agreed to cooperate fully with the U.S. Despite the promise of cooperation, martial law was declared September 3, 1915 and would continue until 1929.

Back in Washington, the Wilson Administration was drafting a treaty that would legalize the occupation. This new treaty was similar to the July 1914 treaty but with additions that would allow for a financial advisor appointed by the U.S. president, establishment of a constabulary organized and staffed by Americans, settlement of foreign claims, and American control of public works. Although Dartiguenave supported the treaty, the Haitian legislature refused to ratify it. Caperton pressured the senators that were holding out on signing the treaty, and it was passed a week later.

The Wilson Administration also aimed to implement a new Haitian constitution that explicitly allowed for foreign land ownership and would validate the legal and constitutional issues of the intervention. All of Haiti's 16 constitutions since their independence from France prohibited alien land ownership. Because of this addition, the Haitian National Assembly refused to pass the new constitution in 1917 and instead drafted their own anti-American constitution. Their refusal to cooperate with intervening forces led to the U.S. dissolving the legislative body. Instead, the new constitution would be put to a popular vote. District gendarmerie officers were ordered to arrest anyone who publicly disagreed with the new constitution. The constitution passed with an overwhelming majority, but less than five percent of the population actually voted in the plebiscite.